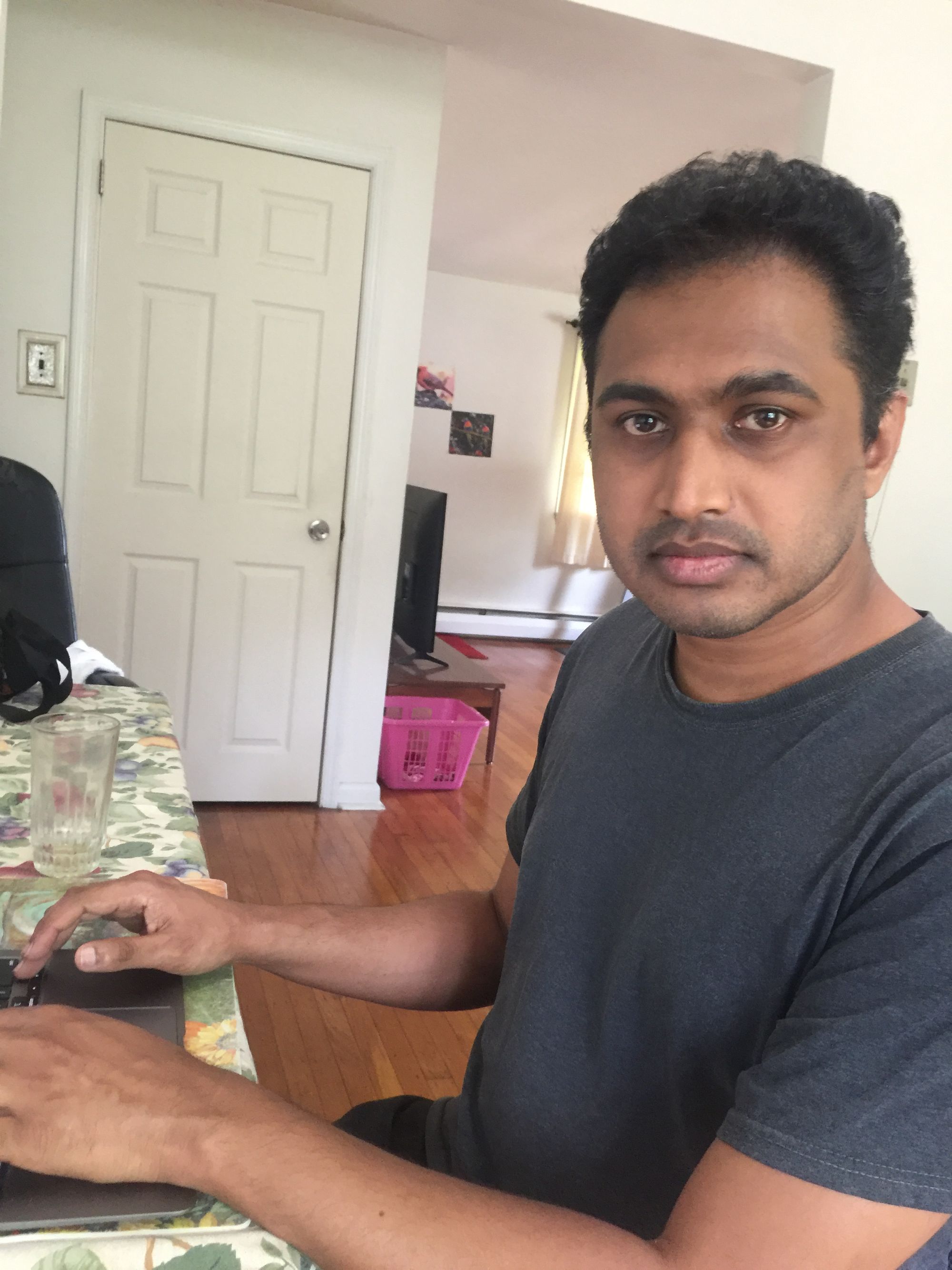

About Ashok

I'm Ashok. Professionally, I advertise myself as someone who builds accessible, engaging, and lasting learning experiences. I also write, aiming to contribute to the field of political philosophy.

I like poems. I like thinking about carefully crafted words which reveal a design, whether that design is from an author or constitutes a hidden truth about the world. I remember being blown away by Ezra Pound's "In a Station of the Metro" in my sophomore year of high school. It just seemed so wild that words could lead you to wrestle with them, play with indeterminacy, and push you to form an image. And then we could debate that image and understand that multiple concerns are at stake. In the case of "The apparition of these faces in the crowd: / Petals on a wet, black bough," one might read it as a comment on natural beauty, or existence flying by, or our daily commute to work. There's so much in so few words.

My formal academic work engages the tradition of political philosophy. I employ a controversial method of reading; I hold that some authors hid their more challenging ideas for a select audience. I find the work of Leo Strauss to be useful in this regard, but I believe an exoteric/esoteric divide is only a beginning for working with the tradition. The political esotericism of some past authors is obvious. Lincoln does not say anything in his pre-war public remarks about banning slavery, whereas his private letters are forthright that slavery and lawfulness cannot be reconciled. Locke continually mentions God, but the materialism inherent in promoting life, liberty, and property belies any serious return to a politics based on faith.

There are less obvious uses of esotericism which lead to questions about how we think through issues. When I worked on Xenophon's portrait of Socrates, I was curious if Xenophon, a worldly man, a general who wanted to create his own civilization, thought Socrates could be noble in any way. In one sense, no, of course not. Socrates simply wouldn't approve of massive bloodletting for honor or any supposed greater notion of honor. In another sense, Socrates was willing to die for the sake of philosophy, and he was particularly astute to how bad philosophers might prevent a "love of wisdom" from ever being a serious occupation. On my reading, Socrates possessed a type of nobility, and it is a nobility directly pertinent to us. I constantly have to deal with people who say reading books is useless and that if we let a child join a sport or make a painting we lower that kid's chances of survival. In the face of rank idiocy thinly disguised as practicality, Socratic narratives stand firm. Political philosophy looks like the most necessary inquiry. We need to know what we're willing to sacrifice for.

I remember being 20 and reading a book and wondering "How does this work?" That question hasn't left me, and I don't think it ever will. My hope is really to send some encouragement to those like my high school and college selves. I distinctly recall having no idea what I was doing or why it was good. A lot of time was wasted and a lot of pain was felt because I thought I had to prove myself. The truth was that the proof was in the meaning. The Greek poiesis isn't just poetry, but making generally. If you make anything, it's as good as a poem, and poetry for the Greeks was no less than Biblical.

Connect

Publications

2018. "Portraits of Ignobility: The Political Thought of Xenophon, and Donald Trump"