On Becoming Spectral: Daniel Clowes' "Ghost World"

Clowes' work is rightfully a classic, but I do have this much to add: I've rarely seen anything as sensitive to the moral lives of teenagers, taking their concerns and claims seriously.

Enid: Actually, he reminds me of that one creep you went out with, that one skinny guy who dressed like he was from the forties...

Becky: Shut up!

-- Daniel Clowes, Ghost World

You already know Ghost World. How, in the summer after graduating high school, longtime friends Enid Coleslaw and Rebecca Doppelmeyer hang out at bad diners, ruthlessly shred those they find pathetic, try to avoid their former classmates, and push poor Josh into their crazy schemes. And you know how their friendship doesn't quite break, but fades away as they choose what they want and grow apart. Clowes' work is rightfully a classic, but I do have this much to add: I've rarely seen anything as sensitive to the moral lives of teenagers, taking their concerns and claims seriously. I can tell you I've been around a lot of adults cruelly dismissive of some of the most earnest, searching young people we have. A lot of adults who think only what they're told at work or what the TV says count for anything.

What struck me hardest during this last reread was how much pain defines Enid and Becky's lives. Both lack mothers. Enid's father cannot and will not relate to her. He can buy her a car and find a record from her childhood, but he's too busy with his own life to notice her self-loathing or her growth. Becky's guardian can't process a thing she says.

Moreover, the future is frightening for them. I confess I would find it difficult to relate to either after I graduated high school. I knew I was going to college. At best, this is a possibility for Enid. For Becky, who ends up working at a bagel shop and dating Josh, it is a non-starter. The future, for all practical purposes, depends on the weirdos they obsess over and their own relationships, real and imagined. It's not that Enid and Becky aren't autonomous, intelligent, and driven. It's that the future, like grief, can be too much for anyone.

Thus, I found myself marveling at their friendship. I too had a best friend in high school, and we spent plenty of time in diners, running into classmates who would get the "fuck that guy" treatment as soon as they were out of earshot. The savagery Enid and Becky unleash on Melorra—budding actress, striving socialite, and television Republican—is timeless. Lots of ink has been spilled on how their tearing down of everyone else is a way of saying "we're not them," an exercise of a measure of control in a world slipping away. I don't think I've seen much commentary pushing back: their friendship works. They don't let each other drown in misery. They don't let neglectful or absent families ruin them. On a smaller scale, having a high school best friend made me believe things were better than they actually were. It wasn't his fault, just a natural byproduct of his being a real friend. I failed to see how vicious and ignorant many others were until much later.

I don't believe the profound melancholy of Ghost World comes from Enid's abusive behavior toward Becky, or Becky's worshipful approach to Enid. (The last panel featuring Becky—she's at Angel's, with Josh, wearing glasses. Where Enid was, at least.) The grief in their lives was too much before their fraying friendship. If Enid and Becky both got straight A's and went to Harvard, they would still have to deal with the shadow of absent mothers, of adults whom they can't talk to. The tragedy, for me, is that both are insatiably curious, and this has led them so far to bond deeply. But since they have a sense things must change, that same curiosity drives them apart.

Enid shows overt curiosity about diners, misfits, alternative culture, punk, sexuality, her childhood, and college. She prepares well for her college entrance exam, as her overuse of advanced vocabulary demonstrates. There's more, though: I'm sure she's posing when she says certain things don't interest her. She says, for example, she doesn't think much about politics, that it's something guys are into like sports or computers. But then she confesses to having tried to talk about the concept of revolution with her father. I remember that sort of conversation when I was younger, and I recall that getting a usable grasp on a political concept was directly related to the time, knowledge, and sensitivity on the part of the adult being asked. Becky seems more conventionally curious—how are other girls attractive? What are boys and men like, what do they have to say?—but her deepest curiosity is about Enid herself. She knows who had a crush on Enid in 5th grade; she sits and goes through Enid's family photos, showing her knowledge of the Coleslaw household. She accompanies Enid to "Cavetown, USA," and if she can't quite relate to her memories of the park, that's probably because Enid was so small that she herself can only remember so much. In the end, Becky's curiosity about Enid leads her to Josh.

This leads me to wonder about what Becky sees in Enid. Maybe nothing, really. People sometimes imitate each other just because. Maybe Enid's sarcasm and independent streak are motivation enough for Becky. Or maybe there's a feeling of being one of the Coleslaws.

I believe there's something more. Enid is mortified by the prank she pulls on an older gentleman who ran a personals ad, hoping to find someone he glimpsed. She's also obsessed with finding Bob Skeets again, a man she derided as a Don Knotts clone and also prank called. These are, for me, two times Enid has real regret for doing harm and a desire to make things right. Her self-loathing is tied up with believing she only lashes out, whether at misfits, "men," Becky, her father, or Josh. I can imagine that it is near impossible to see oneself as anything other than terrible unless you commit to leaving. Enid testifies to this: "my secret plan was to one day not tell anybody and just get some bus to some random city and become this totally different person... and not come back until I had become this new person."

It is really hard to know you need to be someone different, especially when some think you're in charge (Becky and Josh) or will do whatever it takes to placate you (Dad). It's a knowledge that's a curse, because it isn't knowledge of anything specific, but knowledge about. Knowledge lurking around, acting like a premonition, haunting you.

Becky can't see all this. Enid has to outright say she loathes herself. But Becky must glimpse some of this, knowing where Enid is going. That Enid is going.

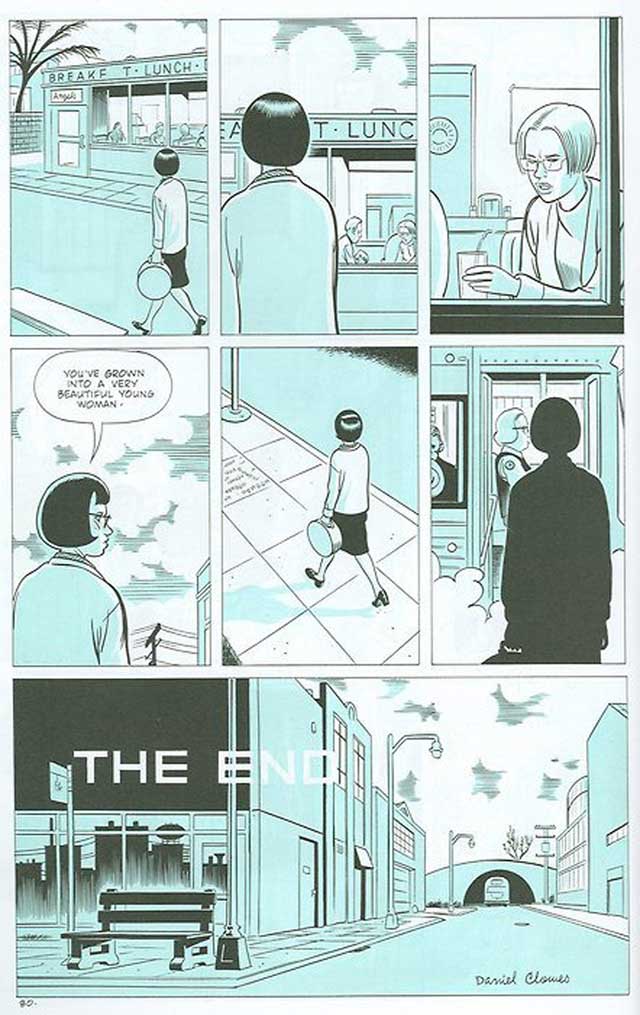

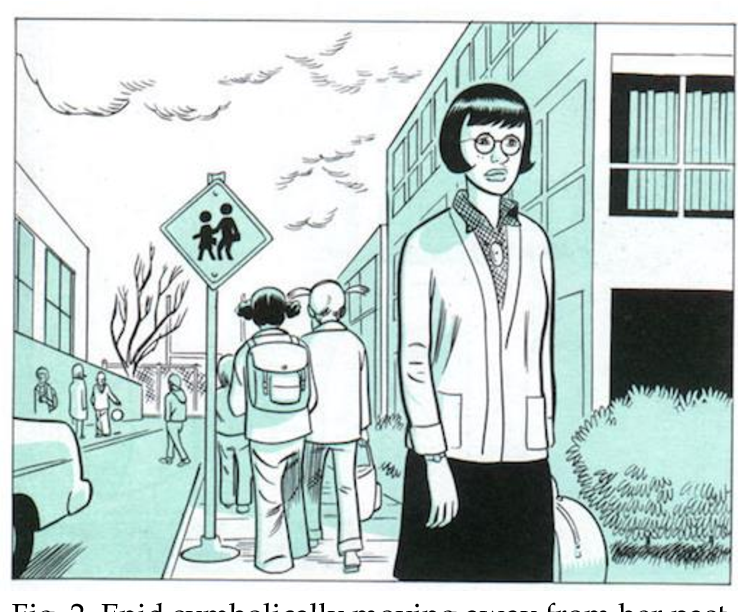

In the last panels of Ghost World, Enid's outfit has changed considerably. There is no hint of previously dressing in a punk or hipster manner. At this point in the narrative, she's been rejected from college. Her dad is back together with a wife she hates. Becky and Josh are together. She's talked to Skeets and gotten a "psychic impression" from him. He presents a vision of a woman from the 20's or 30's, "a woman of intellect and leisure... a sexual libertine," who runs away. For the last 15 panels, she dresses like an adult woman from the past. (1) A neat, simple sweater over a checkered blouse, a black skirt and black pumps, an oval pendant or pin resembling a mirror. Enid's initial expression before she spots Becky one last time and leaves is numb, scared, resigned. The anger and confidence of previous episodes is gone, too. Still, if I had to pick a word to describe her overall look, I'd say "matronly."

The thing about adulthood is you have to guess at who you can be. You end up guessing at what Mom, say, was like. Even while learning from experience, you're still trying to figure out what you need, what it means to make a decision and commit. Part of me wants to indulge a conspiracy theory, that Enid did get accepted to college, but chose to say otherwise. College doesn't mean much if it's all Dad's idea, and burdening Becky with your life after she openly says "I just want it to be like it was in high school" isn't good. Still, same difference—either way, Enid has to confront disorienting losses, a world she knew proving it can't give her anything.

I feel like a large part of becoming older is denying where we are has nothing for us. I don't want to leave what's comfortable for the sake of uncertain goods. What makes Enid heroic despite all the callous, awful stuff she does and says is that she chooses adulthood. Ghost World makes it abundantly clear that this isn't a choice all of us make. We mostly go where our needs are met, not trying to figure out what those needs could be in the first place.

With 55 applications out, I should be getting ready to move. I don't plan on stopping the applications until I get a job I want. At the same time, I'm haunted by my failure to make Dallas a true home. I know I had to be different—more open, outgoing, helpful—and all the same, I know this area reduced my opportunities for being precisely those things.

I'm staring at Clowes' last panel, where the bus Enid is on drives out of town. The bus is the vanishing point; the street it goes down is wide, clear, and open. The sky is cloudy but bright. The bench near the stop, where "Norman" sat, where Enid in a moment of exhaustion told Becky she wouldn't go to college, rests in front of glass reflecting a silhouette of their town. The very first panel of Ghost World is nearly all dark and aquamarine, depicting their neighborhood, rich with comically creepy detail: a trash can badly placed in front of a gate stands out. It's so hard to let go, to realize you're only loving what you know. But pretty soon I'll be on a bus myself.

Image Credits

- Top image, Enid making a call – from Fantagraphics Books, Inc. on Flickr.

- The last page of Ghost World – from The Comics Grid, specifically Paddy Johnston's "Exploring Ghost Worlds: A Review of the Daniel Clowes' Reader"

- Detail of Enid walking to the bus, leaving for good – from Semantic Scholar, specifically G. Rizzi's "Last Stop: This Town. Sameness, Suburbs and Spectrality in Daniel Clowes's Ghost World"

Notes

(1) This summary of the final pages aligns with Ken Parille's "Ghost World at Twenty: Daniel Clowes Dialogue," cited below. He makes the essential points briefly and clearly.

Bibliography

Parille, Ken. "Ghost World at Twenty: Daniel Clowes’s Dialogue." The Comics Journal, 18 Dec 2017. https://www.tcj.com/ghost-world-at-twenty-daniel-clowess-dialogue/

Rife, Katie. "20 years on, a self-proclaimed Enid looks back at Ghost World." The Onion A.V. Club, 01 Dec 2021. https://www.avclub.com/20-years-on-a-self-proclaimed-enid-looks-back-at-ghost-1848132541