Elitism, Pluralism, & Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò's "Elite Capture"

Politics isn't a game, even though parts of it play like one.

I thoroughly enjoyed Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò's Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else). I want to reflect on how it has influenced my approach to teaching Federal Government. Táíwò responds to critiques of identity politics–e.g. maybe it is too watered down a version of "orthodox left politics" to be useful, maybe it is actually a tool for maintaining "class domination over the working class"–by asserting that what has happened to identity politics is elite capture. (1) Elites in developing nations find ways to steer aid meant to uplift the poor to themselves. Similarly, identity politics, by deferring to voices which do not have the same urgency as others, can reinforce a marginalization it originally meant to combat.

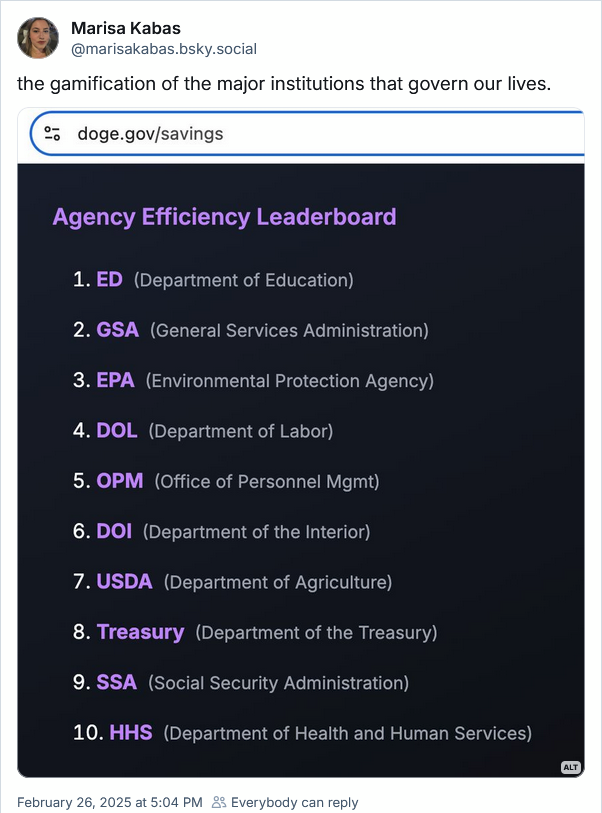

I found Táíwò's section on video games and capitalism, in which he uses insights from C. Thi Nguyen, especially fruitful. As I thought about our world, where we observe the most powerful entities cut foreign and domestic spending like a video game (fig 1), it occurred to me that I had to talk about how extensive this sort of thinking is. The textbook I use, American Government 3e, has a short but rich section on two theories of who rules. These theories are called elitism and pluralism. They are, for the time being, different from elite capture specifically.

To introduce these theories simply, who rules? Is it the elites? Have elites always used the government as an instrument of their will? Or can we posit that pluralism is how things work? It does seem a number of groups find their way to common ground with regard to many issues. In either case, our gamified way of thinking has to be scrutinized. Do we really know what we are doing with either hypothesis?

"Who Governs?," Section 1.2 of the American Government 3e textbook, discusses Elitism vs. Pluralism. (2) These serve as hypotheses about how government works as well as possible prescriptions. Elitism is not just the question "Do elites rule?" After all, whether we speak about the Framers, Ivy League graduates, or monopolists, they had or have disproportionate power over how laws are made and executed. Elitism is also crucial to identifying a prescription. Perhaps elites have far too much influence and require not only opposition but structural change. Or matters exist where a decision made on the basis of popularity could prove fatal to the country.

Similarly, pluralism asks how it is even possible that various groups can govern. Pluralism posits that "competing interest groups who share influence in government" do have decisive political power, although it does not certainly feel that way nowadays. (3) The theory puts forth an answer to how this might work. Americans belong to different interest groups and it does seem that those groups have found solutions which work for everyone. The conflict between those groups, then, shapes policy. Pluralist theory can lend itself to appreciating democratic norms and virtues which enable healthy competition despite high stakes.

Again, we note that both theories function as explanatory and prescriptive. When we ask why people are enamored of elite theory, it is not only because that theory fits the facts. Obviously "the elite... secure for themselves important positions in politics," using "this power to make decisions and allocate resources in ways that benefit them." No one with any sense will argue against this sentence: "Politicians do the bidding of the wealthy instead of attending to the needs of ordinary people, and order is maintained by force." (4) But none of this is why people argue for elite theory today! Ask people in general whether elites rule, and you are treated to conspiracy theories, assertions that someone is being kept down because of an elite specifically, and even apologia for the power of some elites considered allies. With regard to that last point, I have heard people vigorously defend Mr. Musk as he fires people close to them. Elite theory gives reassuring answers when used in a crudely prescriptive way. It does tell some to find the right boot to lick while it tells others that there is nothing they can do about their situation except complain. A few, of course, realize that exclusive rule of the elites requires a fight.

Pluralist theory looks completely invisible right now. No one serious sees interest groups in a competition which could resolve in a healthy manner. I don't just think this is because of the collapse of Congress as an institution or the misuse of SCOTUS' power. I believe there is something fatally flawed in our thinking, too. Elite theory is extremely simple. There are hierarchies, there are those with power, and the impact on the rest of us is visible and has a clearly traceable cause. If different interest groups are influencing each other in different ways, that is much harder to track, even if it resolves in a way all of us recognize. You would need to appreciate a species of complexity many dismiss as naive.

We do not live in a world where plenty play video games and become influenced by their logic. We live in a world that for a long time has promised us success if we think of it as a game. For example, you want to get ahead at work. You do not treat people well or build a project which will help your neighbors immensely. You instead focus on getting a certification which will impress whether or not you possess the relevant skills. This is video game thinking–e.g. do the right thing, expect and depend upon the reward–and it has been around for centuries. I believe you could say that the rich, spoiled youths who attracted Socrates thought that if they knew the correct words, they could get anything. However, this notion that correct actions should yield useful information or eventual rewards is especially pronounced in late capitalism.

Táíwò, following Nguyen, notes that "game worlds" do have "lower stakes" and "artificial clarity" in contrast with "real worlds." (5) This might tempt us to think that gamification could not possibly be accurate. For example, people can tell they will die in this life as opposed to a video game; they will use strategies that take their survival seriously. Unfortunately, we see lots of people behave counterproductively because there is enough "overlap" between game worlds and real worlds to obfuscate questions of value. This is a process called "value capture," "by which we begin with rich and subtle values, encounter simplified versions of them in the social wild, and revise our values in the direction of simplicity–thus rendering them inadequate." Táíwò says capitalism is a system which does this simplification and revision of values, rewarding "the relentless and single-minded pursuit of profit and growth." (6)

That is fair, but I want to go back to the elitism/pluralism debate, because game logic can be thought to feature prominently there. Elitism and game logic go very closely together, especially when we consider the power fantasy video games let players indulge. Players get no less than godlike powers and are encouraged to unleash them in spectacular ways. That is only the most visible manifestation of a more common tendency, of course. What is most relevant for us is that elite theory fits too easily into game logic. Even though it has tremendous explanatory power, even though I think it is basically correct, it has all the wrong elements at play (no pun intended). It uses tools which in another context produce artificial clarity. A focus on elites allows one to indulge one's own irrelevance; a focus on the power of others can lead one to think one has no potential for power; measuring impacts globally is necessary, but if it leads one to believe all personal concerns are invalid, that is despair.

And maybe worst of all, it blinds us to the existence of pluralism.

In Section 1.2, American Government 3e does not describe civil rights as a pluralist movement in any significant detail. This does seem a massive injustice to pluralist theory, as it looks like competing interest groups did find a way to make America a true democracy for the first time in its existence. Civil Rights entailed no less a massive change in the entire nation's view of the Constitution. How can we learn to appreciate the complexity of pluralism in general?

I believe the only way to effectively do this is to practice organization and politics. One has to learn through experience what one can compromise on and what one cannot. This does not mean that all values are up for grabs from the start–far from it! More that some fights which seem like they are inevitable are not, for example when relevant actors understand how they are advancing each other's goals. And that some fights do have to be had among those who agree, because those greedy for power can use agreement to only steal power and nothing more. The complexity of pluralism, in short, demands the practice of politics.

Politics isn't a game, even though parts of it play like one. A lot of listening and good faith are required. They are what creates the complexity, what dissolves "artificial clarity." You can't just say to yourself "do this, it's good for me." There are other people who depend on you, and that balancing act among various needs often requires more than simple hierarchical declarations. Whereas you can write a book about elites by following the logic of their power, a book about democratic rivals has to emerge from documenting the experiences. Everyone is learning to see as everyone else.

References

(1) Olúfẹ́mi O. Táíwò, Elite Capture: How the Powerful Took Over Identity Politics (And Everything Else). Chicago: Haymarket, 2022. p. 6.

(2) Krutz, Glen and Waskiewicz, Sylvie, American Government 3e (2021). Open Access Textbooks. Accessed February 27, 2025. https://openstax.org/books/american-government-3e/pages/1-2-who-governs-elitism-pluralism-and-tradeoffs

(3) Ibid.

(4) Ibid.

(5) Táíwò, 50.

(6) Ibid, 52.