Find Your Voice

How do I convince students to write like they will be heard?

Writing resources I'm using to teach

You might have the same problem I have. How do I convince students to write like they will be heard? How do I get them to believe they can craft something which will last?

A few resources I am finding useful at the present moment:

- Porochista Khakpour, "Just (Don't) Do It" – She connects her strivings with the American Dream and shows just how ableist our ethos is. There's so much here that's relatable: overachieving, faking productivity, a deathly fear of humiliation, an inability to understand one's own accomplishment, one's immigrant status. I've written on how this essay was received by one of my classes.

- Sam Thielman on Homelessness – you should read everything Spencer Ackerman has to say about the radicalization of the military, but scroll down and let Sam's paragraphs on Yusuf and Fulton Street hit like a truck. For my students, this has been the beginning of the end of the ridiculous idea that one shouldn't write in the first person.

- Alexander Chee, "The Mysterious Art of Teaching" – I'm going to start using this in my classes, too. I feel like the most powerful lesson is near the start of the piece. Chee didn't change how he wrote because of the grades he got. He perfected his own wonderment.

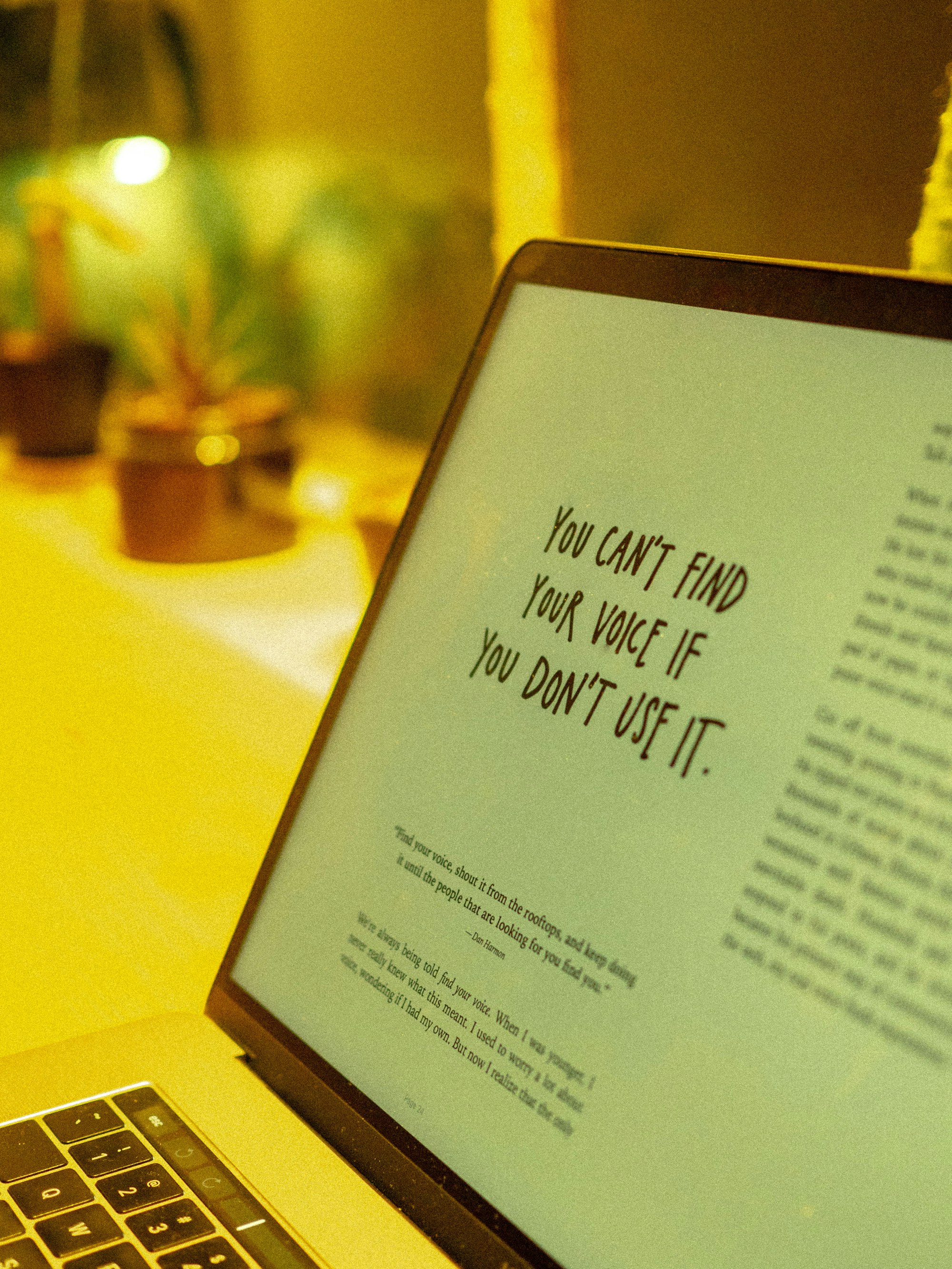

Find Your Voice

The task of this short essay is twofold. First, it aims to encourage those of you who write to keep doing it. Second, to convince those who can't be bothered that something important is at stake. I don't know if I'm up to the task, unless failing often in infinite ways counts. For a long time, my words were far too strict. I wrote in the spirit taught in high school and blinded myself to what the writers I admired did. (1) Later, I became incoherent. I wrote too much and thought highly of those more clever than wise. (2) Now, the problem is boring my reader. After all, who wants to hear about writing?

One neat thing about getting older is also a curse. I don't have to worry about being boring. I know what I have to say has import.

To be sure, this is a recent realization of mine. For years, I believed well-read scholarly misanthropes. Surrounded by scorners of self-esteem, I thought those who talked about their own lives with confidence were vacuous. I couldn't tell you exactly why. I just "knew" that real artists could represent other voices. In fact, they must be so busy giving voice to others they could not talk about themselves. The complex of the authorial self could only be reconstructed from a critical analysis of their oeuvre. (3)

Now I know two things. First, there can be a lot of egotism and fear in talking about everything else but yourself. Second, it is urgent to find a voice so one can start developing it. So much of our world devotes itself to breaking the energy, ends, and power of others. "Find your voice" is far from narcissism when choices and exploitation are difficult to distinguish.

James Baldwin wrote a few powerful pages on the creative process, as one would expect from him. (4) His initial point, that an artist must "actively cultivate... the state of being alone," I've resisted for a number of years. I've resisted it for the same reasons you have--being alone sucks--but I have other views which led me astray. First, I don't know if I should call myself an artist. When I do what I do well, people understand the centrality of moderation in classical thought or more acutely observe how rights work. Is that art? Second, I do believe most in this day and age are desperately alone. The constancy of texting and scrolling has more in common with panic than developing a public persona or meaningful relationships. If people are already alone, why cultivate the state of being alone?

Baldwin, of course, is right. By "aloneness" he means an "extreme state," one like "birth, suffering, love, and death." At those times, you have to confront who you are. (5) We need to be "writing to tell the truth about ourselves, and the truth about us is always at variance with what we wish to be." Traditions and comfortable standards are put aside; statements from enemies can matter more than those of friends. The artist dissects their own delusions and shows others how everyday life can be a cruel trap.

You might ask what any of this has to do with you. You've got a prompt such as "Discuss the causes of the American Revolution" in front of you. I can't tell you that strictly following that prompt leads to artistry, a radical revealing of the truth. I can tell you how I'd apprach it now. Imagine being taxed by an all-powerful figure on another continent, one who asserts you are obligated to them and them alone. Imagine that people around you vigorously debate the nature of freedom and rights, as if they know everything has to change. As if they knew they were a part of that.

Notes

(1) It did not help that the writers I admired in high school were all snark, no substance. I read a lot of National Review and The Weekly Standard.

(2) A number of my professors were completely convinced that "great" books could be deciphered like a cryptogram. Their confidence was infectious, but they found themselves unable to write. The history of thought, it turns out, does not yield much if reduced to a puzzle.

(3) Walter Kaufmann's Introduction to The Portable Nietzsche asserts that Nietzsche is doing something in this vein. Of course, Nietzsche actually has something to say. Full citation: Nietzsche, Friedrich. 1977. The Portable Nietzsche. Translated by Walter Kaufmann. New York: Penguin.

(4) All quotes which follow are from Baldwin's linked essay.

(5) It says something about how we treat love that love for many is not particularly self-reflective.