Kant and Jefferson on Enlightenment

Today I want to talk about a little bit of the rhetoric Kant and Jefferson use to advance Enlightenment ideals. Some scholars assume that because ideals of universal education and technological progress won out years ago, we have an assessment of their legacy ready at hand.

Today I want to talk about a little bit of the rhetoric Kant and Jefferson use to advance Enlightenment ideals. Some scholars assume that because ideals of universal education and technological progress won out years ago, we have an assessment of their legacy ready at hand.

I feel like this is not the best approach? That it can lead to thinking some absurd happening on the news was caused directly by an idea from decades ago. A better approach is to ask what sort of citizen Kant and Jefferson envisioned. If the world has been influenced by their ideas, what are we supposed to be doing? What is the world supposed to look like?

I think that does more justice to what they advance. It allows us to separately talk about issues as we experience them, and then do the thorny, imperfect work of trying to craft a dialogue with the past. Without further ado:

Kant and Jefferson on Enlightenment

Enlightenment is man's release from his self-incurred immaturity. Immaturity is man's inability to make use of his understanding without direction from another. This immaturity is self-imposed when its cause lies not in lack of reason but in lack of resolution and courage to use it without direction from another. Sapere aude! "Have courage to use your own reason!" -- that is the motto of enlightenment.

—Immanuel Kant, "What is Enlightenment?"

Kant declares maturity the ability “to make use of… understanding without direction from another.”

To me, this appears a strange definition of maturity. My freshman year of college, I sat around with some friends and talked about people who changed after high school. It was agreed that those who were overly hostile or awkward, but had learned to be more civil in public, had grown in some way.

For the most part, that’s “maturity.” Can someone show an awareness of standards? Follow rules? Take care of their immediate responsibilities? Then we hold that they’re “mature.”

Kant’s definition detonates ours. Using one’s understanding independently takes precedence over following rules. He goes further: “enlightenment” is about having the courage to use one’s own reason.

Does this mean everyone I’ve thought maladjusted was actually courageous and mature? Kant, at least in theory, is open to this possibility.

It’s a possibility I need to embrace more. Kant’s “What is Enlightenment?” sets forth a high standard for being a good citizen. Inasmuch as you can conceive yourself a “scholar,” having expertise on matters of public concern, you have a duty to provide your informed opinion. Sure, if you’re an officer in the military, you had better obey your superior’s command. But if you can also prove supplies are inadequate, recruits are being bullied and harassed, the generals have insufficient education, and the military’s goals are counterproductive and dangerous to civil society, then you have a duty to present your findings.

This is an incredibly high standard for serious citizenship, but in theory, anyone can be an expert. Kant says they have to present their case before the “reading public.” If one can conceive of universal literacy, then this is everyone. I tend to believe that both the depth of duty—one is obligated to say what harm could be prevented, what could be improved—and the scope of the “reading public” render moot a number of debates about the specific form of government Kant wants. “What is Enlightenment?” courts some fairly radical values, ones if acted upon would make present-day democracies far more democratic.

***

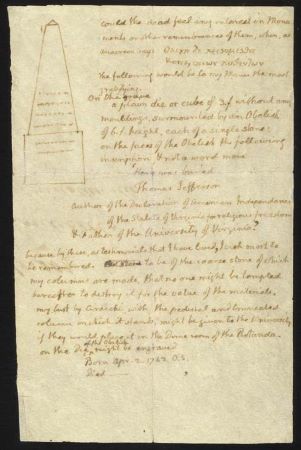

Kant’s rhetoric about “maturity” is one way of articulating an Enlightenment vision for citizenship. Another path lies in the epitaph Thomas Jefferson wrote for his own grave. I remember being introduced to this in Alan Tarr’s American Political Thought class. A good part of that class sincerely read as much Jefferson and Tocqueville as they could. I can’t help but feel that seeing what a few well-ordered words can do inspired them.

Here was buried Thomas Jefferson Author of the Declaration of American Independence of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom & Father of the University of Virginia

The epitaph lists three accomplishments, each one building on the other. I hold a progressive narrative connects Jefferson’s choices.

Author of the Declaration of American Independence. Not just the writer of a document men in powered wigs signed. “Author” has overtones of originator, inventor, creator. The desire for independence was there, but independence itself had not been articulated.

What does it mean to declare independence? Some are tempted to get too clever with the history and the text. They’ll argue that the words everyone considers immortal—We hold these truths to be self-evident, that all men are created equal, that they are endowed by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights, that among these are Life, Liberty and the pursuit of Happiness—do not matter as much as whatever specific action of Parliament or the King the colonists were angry about at that moment. It is true the Declaration of Independence lists a host of complaints, but those complaints don’t point in the direction of “fixable.” Rather, they add up to a clear statement that it can be necessary to overthrow one’s ruler and govern oneself.

All the same, I know it’s possible to go too far in the other direction and argue that a comprehensive theory of politics and rights is operative. That a tradition of asking “What is justice?” culminated in conceiving man as a rights-bearing creature, as having metaphysical properties (as John Alvis might say). This leads some to treat the Founders as having both the philosophical depth of Plato and infallibility regarding political matters.

I don’t know what independence truly is. But I imagine that if it is declared, a few things follow. A commitment to being treated justly and treating others justly, with dignity and respect. An idea that certain things unite us as human beings, and they matter far more than nativist, partisan, or imperial claims for the sake of power. And uncertainty from two different sources, as freedom means making one’s own choices and finding out for oneself.

[Author] of the Statute of Virginia for religious freedom. Declaring oneself free is a first step. Recognition of and respect for rights, as incredible as they can be, are also a beginning. Belief, though, introduces a problem of a higher order.

The Statute of Virginia for Religious Freedom is straightforward enough. “No man shall be compelled to frequent or support any religious worship, place, or ministry whatsoever, nor shall be enforced, restrained, molested, or burthened in his body or goods, nor shall otherwise suffer, on account of his religious opinions or belief; but that all men shall be free to profess, and by argument to maintain, their opinions in matters of religion, and that the same shall in no wise diminish, enlarge, or affect their civil capacities.” No one will be “compelled to frequent or support” any institution of religion or be burdened on account of their own beliefs. At a time when Christian Dominionism is a powerful force in American politics, where apocalyptic fantasies fuel the reading of media and events like they’re extensions of the Book of Revelation, Jefferson’s pride in curtailing obnoxious chapters and proselytizers is sobering.

The problem belief introduces might be bigger than even this. Freedom seems to entail believing what you want, finding not only what is good for yourself but is genuinely greater for all. How to reconcile these sorts of claims not only with the rights of others, but the laws themselves?

Religious freedom goes far in addressing this. You could say it is more than a negative right. As Jefferson in the Statute says of God: “the holy author of our religion, who being lord both of body and mind, yet chose not to propagate it by coercions on either, as was in his Almighty power to do, but to extend it by its influence on reason alone.” The last part about “reason alone” was deleted by the Assembly and did not make it into the Statute. But if we’re wondering about what an enlightened citizenry looks like, it is not unreasonable to assume that trust in human rationality underlies our differing beliefs. That the law allows us to choose what we want to believe because it believes us worthy of dignity and respect, capable of justice, able to make difficult choices in the face of cosmic uncertainty.

Father of the University of Virginia. It is not enough to declare independence or believe in reason. What matters is that the use of our rational faculties can produce. One can imagine Jefferson and Franklin as more than Renaissance men. They don’t simply pride themselves on their inventions and discoveries; they want a country where progress multiplies, where people continually experiment and seek solutions.

It was a novel and beautiful vision in the 18th century, but we’ve seen how it can be corrupted. I’m all for teaching students math and science. But when some students go to school for over a decade and have never been exposed to the arts and are kept purposely away from discussion of current events—that’s straight-up wrong. Francis Bacon in his New Atlantis does depict a society where nearly everyone tries to advance technology and who actually rules is obscure, but the dark implications of New Atlantis are nothing compared to our extensive corruption. If you’re outright banning any discussion of racism in public schools while stripping them of funding, and then saying STEM is the only thing kids should learn, your political agenda is very clear.

Jefferson and Franklin were exceedingly practical, but our present crisis requires a more rigorous treatment of what is practical. I don’t believe teaching the humanities and liberal arts will necessarily save our political institutions. I do believe this, though. Properly used, they open up a space for discussion and dignity that educational institutions are apt to neglect. Most of my time in school, I felt bullied, uninformed, and underutilized. I think now that’s not a coincidence; we’ve lost the spirit of what made the possibility of education so exciting. Why someone would want the maturity of which Kant speaks. The actual good at stake isn’t better semiconductors or the rediscovery of a lost author. It was always about the courage to use one’s own reason.