Philosophy and Advertising

If we do separate philosophy from religion cleanly, then is philosophy relegated to being a cult?

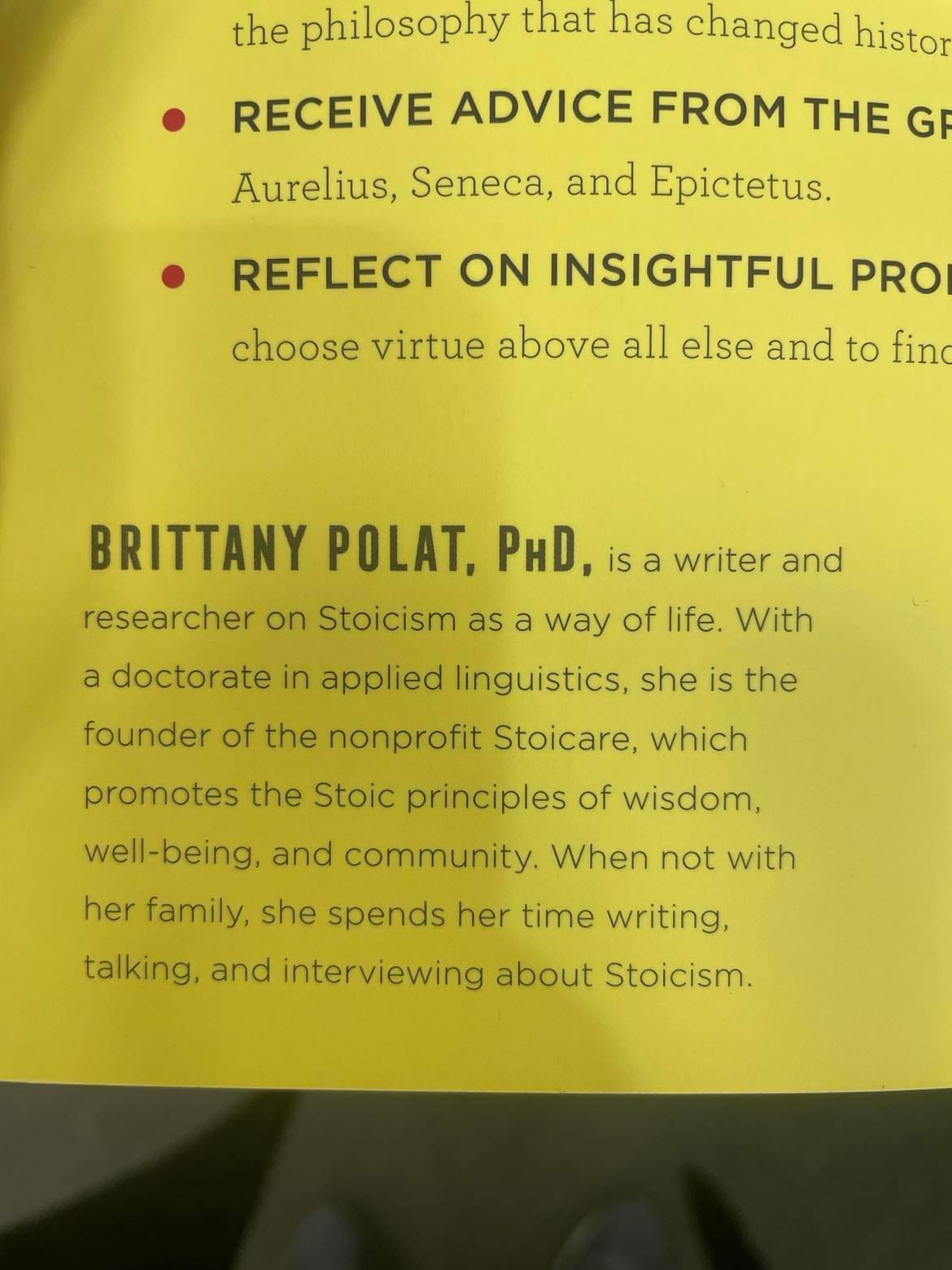

I think we need to talk about philosophy and advertising. Here's an author bio which caused me to raise an eyebrow:

This book cover, um, does not hesitate to tell you that the author is devoted to Stoicism. "Brittany Polat, PhD, is a writer and researcher on Stoicism as a way of life. With a doctorate in applied linguistics, she is the founder of the nonprofit Stoicare, which promotes the Stoic principles of wisdom, well-being, and community. When not with her family, she spends her time writing, talking, and interviewing about Stoicism."

I get it. I've written and continue to write terrible introductions for myself. And I would guess that this was put forth by a rather aggressive marketer, one who didn't want to take any chances and miss eager consumers of a certain philosophical movement.

Still, there's a larger issue here. To what degree is philosophy indistinguishable from religion? How does one begin to separate the two? If we do separate philosophy from religion cleanly, then is philosophy relegated to being a cult?

We can approach this larger issue by stating the obvious. Nothing is gained by having a dialogue reducible to "Stoic? Stoicism! Stoic icsto tosic." However, you might say that loving wisdom does have to start with a name. Maybe a name alone. Since truly philosophical questioning depends on one's devotion to it, one's willingness to step completely into the question, you can't really separate questioning from the questioner. So why can't we start with a name representing ideas practiced by those who are much more thoughtful than I ever will be?

I'm tempted to say you can't just descend into idiocy. Credibility isn't gained from repetition; it's gained from risk. I realize this is not a proposition we would normally entertain. A lot of times, we want confirmation of a thing by seeing that exact thing in the world. We want to equate the grade with knowledge, the degree with a skill, the job itself with qualification. There's a lot more "we mentioned Stoicism, so we must immediately be calmer and wiser" logic in our own lives than we would initially believe.

The notion of philosophical risk is tricky. I feel like it draws on the same reserves that a strong religious faith might draw on, but there are pressing differences. I wouldn't think of trying to convert someone; I do not share testimony, I share experiences; a grounded optimism is not providential. The risk does not concern loyalty to a higher power. It's about whether you can push something sublimely ridiculous into the realm of sense.

That does sound cultish, to be sure. But let's take a simple, famous example: Platonic forms. Here's a notion that in order for us to recognize a couch as a couch, the form of a couch must exist in our minds. That maybe before emerging into this world we knew everything, and then we were born and forgot what/that we knew. Even without sorting through the heavy amount of irony attending Socrates' presentation of the forms, you can see how this as pseudoscience opens up a number of serious and interesting questions. How exactly do we recognize anything? Is that process of learning entirely explainable through social training? What constitutes true knowledge? What might we know in the womb?

It's ridiculous, it's sublime, and any cultish vibes come from the fact the questions are cool. The same holds for more explicitly moralistic ideas, too. I'm not a big fan of Augustine's notion that evil is a privation, but I will say that there are a lot of terrible things which were just one slight tweak away from being very great goods.

At this juncture, we want to know what risk attends philosophy as self-help. It can't be that if someone embraces philosophy wrongly they mess up their lives to an obscene degree. That's not a risk as much as outright failure. The question is what someone wanting self-help is willing to give up in order to see more difficult truths. It can be time, it can involve discipline, it can be a change in habits. But the biggest change has to involve an openness to being wrong.

That's where Stoicism as a near panacea gets very weird. There are a lot of people who want to have more emotional resilience because they'd rather not feel guilt and regret while doing some questionable things. I think philosophy has to be outright that, like therapy, some prior beliefs and attitudes are going to found wanting. That we're going to have to apologize and make restitution because we screwed up and doubled down. The risk philosophy as self-help demands is justice.

I doubt I'll see that on a book jacket any time soon.