Yosa Buson, "The old fisherman"

I wonder if this is aging: refusing to look elsewhere, focusing on the object in front.

Hi all –

Two things are sitting upon my mind. One I won't shut up about: I'm really worried that people are going hungry where I am. I've given to the food bank but I know so much more has to be done. We've got to identify needs and act accordingly. Nothing which remedies the situation can be done alone.

The other I'm somewhat quiet about, though I've spoken about it on the blog a few times. I want modules for my courses on current events or big thinkers which will especially resonate. OK, you say, that's what every teacher always wants. Why is it so important now? Well, I mean, so much is at stake. And because the stakes are enormous, they destroy many of the things we've heard for years. We repeatedly heard it was worthless to study big ideas and questions. But now, STEM majors meant to go into industry can't get jobs. It is clear the Constitution needs to be changed. Experiences of oppression not only need to be documented, but people need to immerse themselves in them, understanding the multitude of ways pain is inflicted. Guess which majors and fields are required for this moment? And guess who will hear that those very majors and fields are useless because of an outdated–maybe never accurate–idea of what pays?

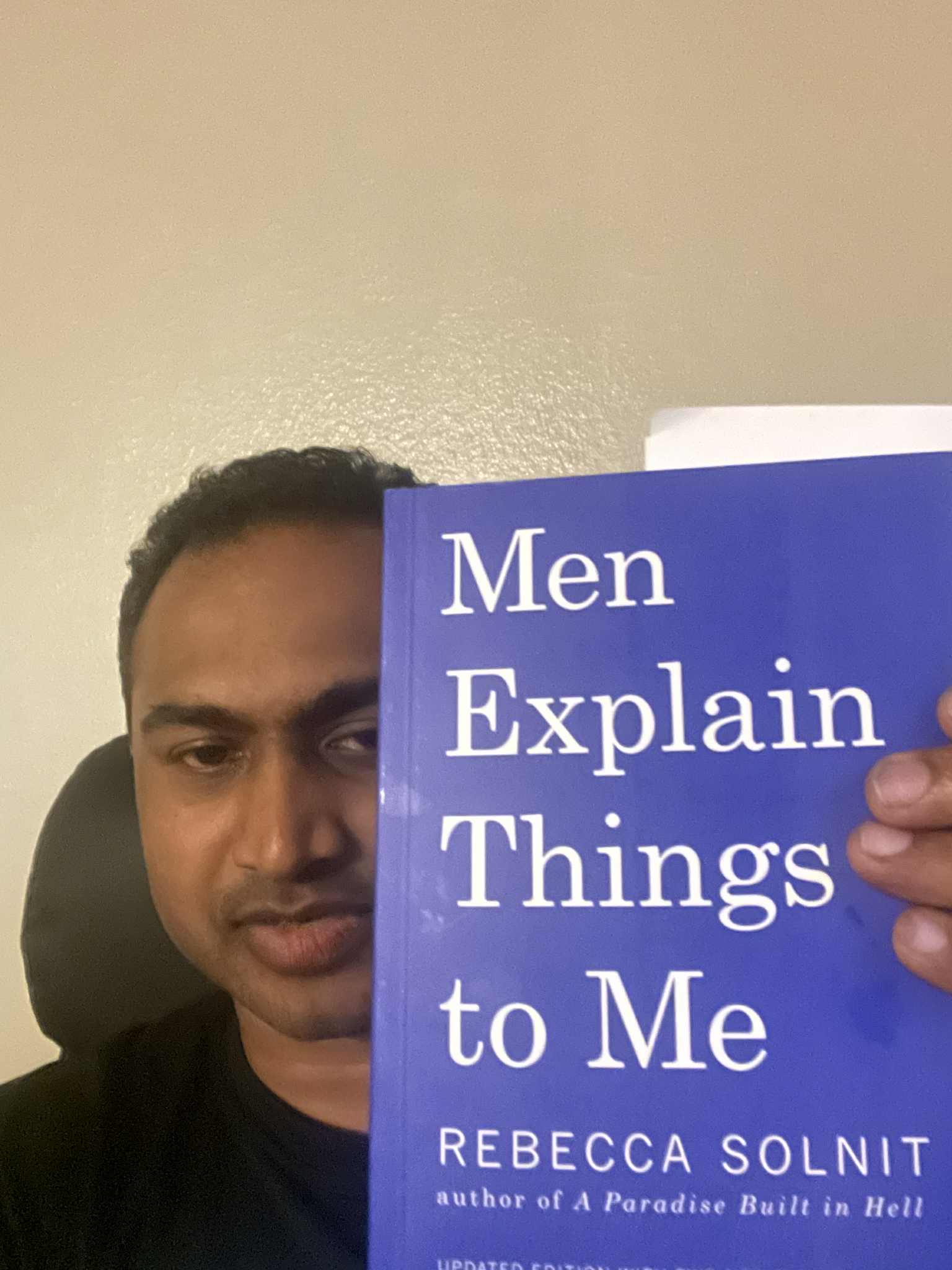

The lack of respect for big ideas and big questions goes hand-in-hand with wanting certain people to not be heard. And I think that's one thing which led me to buy a copy of Rebecca Solnit's Men Explain Things to Me and promptly read the title essay. I'm fascinated with the arrogance and bluntness some men use to opine on topics they know less than nothing about. Some minds are blindly set on domination. Is it possible to shame that behavior?

Other ways of shutting people down can be more subtle. The ideas in Tressie McMillan Cottom's "The Hustle Economy" should be discussed far and wide. There's an economy which works for people who have already made it, and then the subprime, informal economy using inclusion as a weapon. Whether we're speaking of business loans that can hit 50% interest rates or apps which demand incredible labor for low pay, we're speaking of a form of oppression which exhausts you into silence or resentment.

Before I talk about the poem, I'd like to leave you with this link to a fascinating bit of D.C. and Black history. Kaitlyn Greenidge leaves no stone unturned in this short Substack essay about how the current assault on Black D.C. residents is an age-old attack. I'm impressed by how she identifies and details the primordial racism at play.

Yosa Buson, "The old fisherman"

"The old fisherman / unalterably intent... / cold evening rain." "Cold evening rain" is not "in the cold evening rain." The awfulness of the weather and the image of an old man waiting for a fish are equivalent.

"The old fisherman." I recall my father staring at the television for hours on end well before he became truly old. Sitting on a brown, dilapidated couch, pressing the remote occasionally, obeying the same routine of programs. The living room had large, bright windows overlooking athletic fields. Anytime he wanted to see people play a game outside, he could. That never happened.

I wonder if this is aging: refusing to look elsewhere, focusing on the object in front.

What was he looking at? Nowadays, for our elderly, the answer leans toward titillation. You may be thrown into a panic, or made angry, or even brought joy, but the object in front never fails to excite emotion as a narcotic would. Truth be told, the emotion could be a downer, too. Not a particularly excited state, but not quite boredom.

There's a deeper answer. (One which, if pursued thoroughly, challenges the notion that developments in technology account for our present radicalization.) You can unearth it by asking about our own behavior, young and old. Why do we doomscroll? Why is it interwoven with photos of the extremely attractive? We're fixated on longings of which we aren't fully conscious. These longings can consume us as we age. The half-consciousness of them–maybe we will receive a miracle, maybe we can dull our fragmented minds–creates the object in front, whether that object is a television or water dimly reflecting you.

The old fisherman Yosa Buson (tr. Kenneth Yasuda) The old fisherman unalterably intent… cold evening rain

"Unalterably intent." Then again, the old fisherman has a goal. Or so he thinks. Just one more fish.

I can say it is addiction, but that doesn't do justice to the situation. What if he needs that fish to survive? What if this is the moment the fish will bite?

There are times we have to be desperate, be little more than an addict, to see things through. You don't create a body of work, after all, by writing or drawing or playing perfectly. Usually, it is thousands of drafts deserving of annihilation, a mania begging for witness to its witlessness.

Buson documents this fisherman. Is he also in the cold, evening rain? It seems so. You need to see the fisherman's face to mark the intent. What else is unalterable here–what else has been committed to more permanent memory? What does it mean to willingly inherit misery?

"Cold evening rain." The water in front of the fisherman comes to surround him, but also defines the world for the rest of us, including the poet. The fixation, the layered, possibly unknowable longing, is reality.